From

Ruins of Afghan Buddhas, a History Grows

Published:

December 6, 2006

A

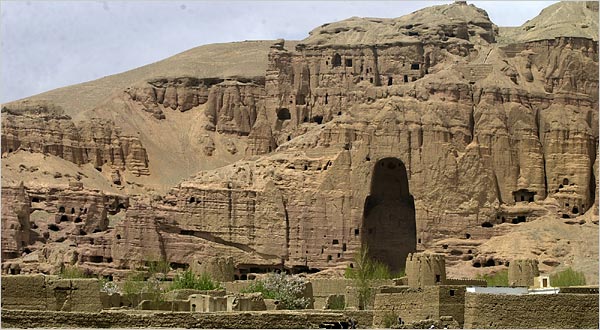

huge empty niche now punctuates the majestic Bamiyan Valley of

Afghanistan where the giant western Buddha, one of two, once stood.

By

CARLOTTA GALL

Published: December 6, 2006

BAMIYAN, Afghanistan — The empty niches that once held Bamiyan’s

colossal Buddhas now gape in the rock face — a silent cry

at the terrible destruction wrought on this fabled valley and

its 1,500-year-old treasures, once the largest standing Buddha

statues in the world.

The

western Buddha as it stood from A.D. 554 until March 2001, when

it was destroyed by the Taliban. At 180 feet, it was the larger

of the two.

It

was in March 2001, when the Taliban and their sponsors in Al Qaeda

were at the zenith of their power in Afghanistan, that militiamen,

acting on an edict to take down the “gods of the infidels,”

laid explosives at the base and the shoulders of the two Buddhas

and blew them to pieces. To the outraged outside world, the act

encapsulated the horrors of the Islamic fundamentalist government.

Even Genghis Khan, who laid waste to this valley’s towns

and population in the 13th century, had left the Buddhas standing.

Five

years after the Taliban were ousted from power, Bamiyan’s

Buddhist relics are once again the focus of debate: Is it possible

to restore the great Buddhas? And, if so, can the extraordinary

investment that would be required be justified in a country crippled

by poverty and a continued Taliban insurgency in the south and

that is, after all, overwhelmingly Muslim?

This

valley about 140 miles northwest of Kabul, where in the sixth

century tens of thousands of pilgrims flocked to worship at its

temples and monasteries and meditate in its rock caves, is attracting

new international attention.

In

2003, the United Nations designated the Bamiyan ruins a World

Heritage site, but also listed them as endangered, because of

their fragile condition, vulnerability to looters and pressures

from a post-Taliban boom in construction and tourism. Intensive

efforts have been under way to stabilize what remains of the cliff

sculptures and murals.

Meanwhile,

archaeologists have been taking advantage of the greatly increased

access that became possible once the statues were gone to make

new discoveries — and to pursue ancient tales of a third

giant Buddha, possibly buried between the two that were destroyed.

“The

history of Bamiyan is beginning to be revealed, in a concrete

sense, for the first time through both works of conservation and

excavations of archaeological remains,” said Kasaku Maeda,

a Japanese historian who has studied Bamiyan for more than 40

years.

Unesco has been overseeing a program of emergency repairs to the

niches over the last few years, drawing teams of archaeologists

and conservationists from all over the world. “The site is

in danger,” said Masanori Nagaoka, a cultural program specialist

at Unesco’s Kabul office.

Gedeone

Tonoli, a tunnel engineer from Italy, has been overseeing the

most urgent task: securing the cracking cliff face. One morning

two Italian mountain climbers swung on ropes at the top of the

niche that held the eastern Buddha, which, at an astounding 125

feet tall, was the smaller of the two. Wire netting covered the

back wall of the niche, which still occasionally rattles with

falling rocks and stones. A great scar marks the inner left wall

where the explosion tore away the side of the niche, threatening

the whole cliff.

The

right side of the niche, however, has been stable for two years,

anchored with steel rods and tons of concrete pumped into the

fissures. Tiny glass slides are taped to the rock, and sensors

linked to a computer keep track of every tremble in the cliff

face. Before, Mr. Tonoli said, “you could see the sky here

and birds were flying in.”

At

the base of what, at 180 feet, had been the larger Buddha, workers

were still shoveling away at rubble left from the explosions.

German restorers from the International Council on Monuments and

Sites have spent two years carefully sorting through the debris

from both Buddhas, lifting out the largest sections by crane —

some weigh 70, even 90 tons — and placing them under cover,

because the soft stone disintegrates in rain or snow. The smaller

fragments and mounds of dust are carefully piled up at the side.

Reports

that the Taliban had taken away 40 truckloads of the stone from

the statues to sell were not true, said Edmund Melzl, a restorer.

“From the volume we think we have everything,” he said.

Yet only 60 percent of that volume is stone, he added. The rest

crumbled to dust in the explosions.

A

continuing paradox is that the destruction of the Buddhas has

in a way aided archaeologists in their investigations. For example,

carbon dating of fragments of the plaster surface of the Buddhas

was able to pinpoint the construction of the smaller one to 507,

and the larger one to 554. Previous estimates had varied over

200 years.

At the

Foot of Bamiyan

The Buddhas were only roughly carved in the rock, which was then

covered in a mud plaster mixed with straw and horsehair molded to

depict the folds of their robes and then painted in bright colors.

Workers have recovered nearly 3,000 pieces of the surface plaster,

some with traces of paint, as well as the wooden pegs and rope that

were laid across the bodies to hold the plaster to the statue. The

dryness of Afghanistan’s climate and the depth of the niches

helped protect the statues and preserve the wood and rope.

The

larger Buddha was painted carmine red and the smaller one was

multicolored, Mr. Melzl said.

The

most exciting find, he added, was a reliquary containing three

clay beads, a leaf, clay seals and parts of a Buddhist text written

on bark. The reliquary is thought to have been placed on the chest

of the larger Buddha and plastered over at the time of construction.

The

fragments have been carefully stored while the main task continues:

to gather all the rubble so that the Afghan government and experts

can decide what to do with it. There have been calls to rebuild

the Buddhas, mostly from Afghans who feel that restored statues

would provide a greater tourist attraction, and a righting of

wrongs. Unesco has warned that for Bamiyan to retain its status

as a World Heritage site there must be no new building, only preservation.

Yet the alternative of displaying 200 tons of recovered material

in a museum does not seem feasible, said Michael Petzet, president

of the International Council on Monuments and Sites.

The

one restoration approach considered acceptable by Unesco and other

experts is anastylosis, often used for Greek and Roman temples,

in which the original pieces are reassembled and held together

with a minimum of new material. Michael Urbat, a geologist from

the University of Cologne, has analyzed pieces of the larger Buddha

and from the rock strata has been able to work out what part of

the vast statue they came from.

But

reassembling pieces that can weigh up to 90 tons would be extremely

difficult; Afghanistan does not even have a crane strong enough

to hoist them, Mr. Melzl said. The reconstruction project, which

the governor of Bamiyan Province has estimated would cost $50

million, would probably also become a political issue in this

impoverished Muslim country, where more than 10 percent of the

population remains in need of food aid.

Nevertheless,

the provincial governor, Habiba Sarabi, favors rebuilding the

Buddhas using anastylosis, and said she would propose that the

central government make a formal request to Unesco. Professor

Maeda said he supports the idea of reassembling one of the Buddhas

and leaving the other destroyed as a testament to the crime.

The

government also approved the proposal of the Japanese artist Hiro

Yamagata to mount a $64 million sound-and-laser show starting

in 2009 that would project Buddha images at Bamiyan, powered by

hundreds of windmills that would also supply electricity to surrounding

residents.

Meanwhile,

simply preserving what remains is daunting. Once the niches, grottos

and caves were covered with murals, but 80 percent were obliterated

by the Taliban, Professor Maeda said. Art thieves also did damage,

using ropes to climb into caves 100 feet up on the cliff face

and hacking away priceless medallions depicting seated Buddhas.

One of them made its way to Tokyo, where an art dealer, suspecting

its illicit provenance, showed it to Professor Maeda, who has

managed to retrieve more than 40 stolen artifacts.

“One

day I hope we will return them to Afghanistan,” he said.

He

continues to scour the caves, and finds small joys amid the destruction.

One cave that he first discovered during his first trip here,

in 1964, so blackened by soot from camp fires that the Taliban

and looters passed it by, has revealed fine paintings of tiny

animals — a lion and a wild boar, a monkey, an ox and a griffin

— rare in Buddhist art, but characteristic of Bamiyan, which

combines Indian, Iranian and Gandharan influences.

While

the focus now is on conservation, experts know there is more to

discover. At least two teams of archaeologists are engaged in

a discreet race to discover a third colossal Buddha that may have

once lain between the two standing Buddhas.

The

Chinese monk Xuan Zang visited Bamiyan in 632 and described not

only the two big standing Buddhas, but also a temple some distance

from the royal palace that housed a reclining Buddha about 1,000

feet long. Most experts believe it lay above ground and was long

ago destroyed.

But

two archaeologists, Zemaryalai Tarzi of Afghanistan and Kazuya

Yamauchi of Japan, are busy digging in the hope of finding its

foundations. Mr. Tarzi, who excavated a Buddhist monastery this

year, may have also found the wall of the royal citadel that could

lead the way to the third Buddha. He plans to return next year

to continue digging.