Hidden

text reveals Archimedes' genius

FROM

ancient Syracuse, through the medieval Holy Land to Istanbul

and, finally, California, it has been a long journey for

a musty old prayer book. But what is written on it makes

the journey worthwhile. "This is Archimedes' brain

on parchment," says William Noel, curator of ancient

manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

Hidden beneath the lines of ancient prayers and layers of

dirt, candle wax and mould lies the oldest written account

of the thoughts of the great mathematician.

FROM

ancient Syracuse, through the medieval Holy Land to Istanbul

and, finally, California, it has been a long journey for

a musty old prayer book. But what is written on it makes

the journey worthwhile. "This is Archimedes' brain

on parchment," says William Noel, curator of ancient

manuscripts at the Walters Art Museum in Baltimore, Maryland.

Hidden beneath the lines of ancient prayers and layers of

dirt, candle wax and mould lies the oldest written account

of the thoughts of the great mathematician.

This

invaluable artifact is a classic example of a palimpsest:

a manuscript in which the original text has been scraped

off and overwritten. It was discovered more than a century

ago, but only in the past eight years have scholars uncovered

its secrets. Using advanced imaging techniques, they have

peered behind the 13th-century prayers inscribed on its

surface to reveal the text and diagrams making up seven

of Archimedes' treatises. They include the only known copies

of The Method of Mechanical Theorems, On Floating Bodies

and fragments of The Stomachion in their original Greek.

As

the investigation drew to a close in August, the impact

of these discoveries became clear. What one of the experts

described as "a very drab and dirty object" sheds

fresh light on how Archimedes developed proofs and theorems,

and shows that he may have employed and understood the concept

of infinity more rigorously than previously thought. It

also suggests that Archimedes discovered the field of mathematics

called combinatorics, an important technique in modern computing.

These are remarkable discoveries, yet it is only through

a chain of chance events that the text was discovered at

all.

The

story begins in ancient Greece. Little is known about Archimedes'

life other than that he was born in Syracuse, Sicily, around

287 BC, educated at Alexandria in Egypt and was the son

of an astronomer. He is probably most famous for devising

a way of calculating an object's density. King Hiero asked

Archimedes to see if a crown was made of solid gold or,

as he suspected, a mix of cheaper metals. Legend has it

that Archimedes' moment of inspiration occurred in the bath.

He realised that by dividing his weight by the volume of

water his body displaced, he could to calculate its average

density. The same would work for any object, Hiero's crown

included. In his excitement at solving the problem he is

said to have jumped out of the bath shouting "Eureka!"

Archimedes

wrote his mathematical treatises on scrolls. Though the

originals are all lost, copies had been made onto papyrus

and parchment. Today only three books containing Archimedes'

texts remain: codices A, B and C. Of these, the first two

are medieval Latin translations, held in the Vatican library.

It is now known that the third, codex C, was written on

parchment in Constantinople - the modern-day Turkish city

of Istanbul - around AD 1000. It is the only one containing

The Method and also contains a fragment of The Stomachion.

Somehow, it wound up in the monastery of St Sabas near Jerusalem,

where in 1229 a Christian monk unceremoniously pulled the

manuscript apart, scraped the pages clean, rotated them

by 90 degrees, folded them in two and wrote an orthodox

prayer book called the Euchologion over it.

The

prayer book lost several leaves through heavy use, but remained

otherwise intact and eventually found its way to the Church

of the Holy Sepulchre in Istanbul. There it lay until, in

1906, Johan Ludvig Heiberg, a professor of the history of

mathematics from the University of Copenhagen in Denmark,

studied the manuscript and realised the significance of

the mathematical text faintly visible in the margins and

beneath the prayers. He identified it as containing The

Method, The Stomachion and On Floating Bodies alongside

further works by Archimedes and other unidentified texts.

A

few months later, the manuscript went missing. It resurfaced

briefly when a French family living in Istanbul announced

they had bought it, and there it remained, untouched for

several decades. Descendants tried unsuccessfully to sell

it to public institutions in Paris and London in the early

1990s, and finally, in 1998, offered the manuscript on open

auction at Christie's in New York.

It

sold for $2 million to an anonymous millionaire known as

"Mr B". Fortunately, he turned out to be both

enlightened and generous. He responded to an email from

Noel asking to display the palimpsest at the Walters Art

Museum. That simple request kicked off a new chapter in

the saga: the Archimedes Palimpsest Project. It brought

together an international team of conservators, mathematicians,

imaging experts and physicists to unlock the secrets hidden

within the prayer book. Mr B funded the work, spending almost

as much as he had paid for the manuscript. Many involved

worked for free out of the conviction that Archimedes deserved

to be heard from the grave.

Among

the eager scholars lining up to examine the palimpsest,

one man had a head start. Nigel Wilson, a classics scholar

and retired tutor at Lincoln College, Oxford, UK, had been

asked to examine and describe the palimpsest for Christie's

catalogue, and almost 30 years earlier he had identified

a fragment from a single palimpsest folio - then held at

the University of Cambridge - as containing text by Archimedes.

That folio turned out to be one of the manuscript's missing

pages.

Abigail

Quandt, a senior conservator of rare books and manuscripts

at the Walters Art Museum, took on the painstaking job of

conserving and disbinding the manuscript. Wilson quickly

became part of the project. "I realised at once that

if you could apply even an ultraviolet lamp to the manuscript,

you'd be able to read a great deal more than was read in

1907", when Heiberg was first transcribing the palimpsest.

The

Heiberg translation was a constant reference point for the

team. He had examined the palimpsest using only a magnifying

glass, but it was in considerably better condition then

than it was by the end of the century. At the time, there

were 177 folios, of which three have since been lost. "In

1906, mildew had not yet begun to attack it," says

Wilson. Luckily, Heiberg took several photographs of the

manuscript, which were rediscovered at the Danish Royal

Library in Copenhagen and digitally reproduced. They filled

in some of the gaps where the parchment had been eaten away

by mould.

Most

of the text, however, was retrieved using multispectral

imaging, a technique in which wavelengths of light not visible

to the human eye are beamed at the parchment and the reflected

light is captured and converted by computer into a visible

image. Algorithms then enhanced selected parts of the text,

revealing traces of ink that are too faint to see.

Absorbing

thoughts

This work was led by three imaging specialists: Roger Easton,

professor of imaging at the Rochester Institute of Technology,

New York; Keith Knox from Boeing in Seattle, Washington;

and William Christens-Barry of Equipoise Imaging in Ellicott

City, Maryland. Between them they refined the imaging technique

specifically for the palimpsest by combining two different

wavelengths from the red and blue parts of the spectrum.

The parchment reflected both red and blue light, making

it appear almost white. The pigments in the prayer ink absorbed

these wavelengths and appeared black, while Archimedes'

text absorbed the blue and reflected the red, appearing

as a legible red script.

Yet

some parts of the text remained obscure. Physicist Uwe Bergmann

at the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center in California

read about the problems the imaging project was having in

the German magazine Der Spiegel and thought he might be

able to help. The ink in the script contained iron, and

Bergmann realised that a technique called X-ray fluorescence

might reveal it. X-ray fluorescence relies on the fact that

when an X-ray photon strikes an iron atom it knocks out

an electron, which is immediately replaced by another electron

dropping in from a higher energy state to fill the gap.

This releases a photon of light with a characteristic wavelength.

"We record that flash, note the position where the

X-ray beam struck the page and reconstruct this in a digital

image."

Even

then, the task was far from straightforward, as the inks

used for the prayer book also contained iron. To make matters

worse, several pages had been covered with illustrations

containing metals such as gold, lead and zinc, probably

painted in the 1930s by forgers attempting to increase the

manuscript's value. Despite these problems, Bergmann and

his team managed to decode 15 pages that had failed to yield

their secrets to multi-spectral imaging analysis. Of special

interest were the pages within The Method, in which there

were hints that Archimedes discussed infinity. This was

a huge surprise.

It

has long been accepted wisdom among historians that the

ancient Greeks did not use infinity. Historian Ken Saito

of Osaka Prefecture University in Japan and Reviel Netz,

a professor of classics at Stanford and an expert on pre-modern

mathematics, now think otherwise. Netz edited the Archimedes

text and believes that the great mathematician not only

knew about infinity, but was calculating with it, using

an early form of calculus. "We always knew about Archimedes'

role in perfecting the Greek method of dealing with infinity

in a roundabout way," but now there was evidence of

Archimedes talking about infinity as a kind of number, Netz

says - unique in Greek thought, as far as he can tell.

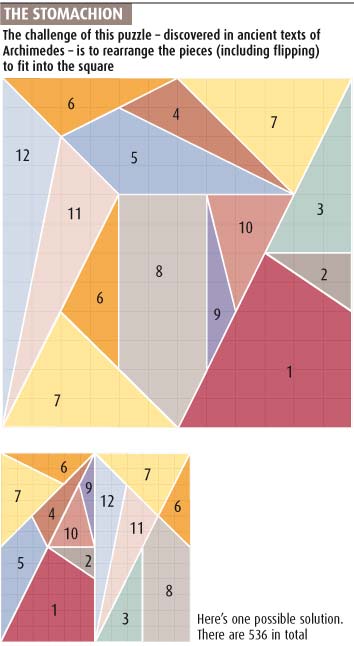

Netz

also proposes an intriguing explanation for the Stomachion

(see Diagram) - the name given to an ancient puzzle, or

"tangram", in one of Archimedes' treatises. A

tangram is a puzzle in which a square is divided into different

geometric shapes and, like a jigsaw, must be put back together.

In the treatise the square is divided into 11 triangles,

two quadrilaterals and a pentagon. Many assumed that Archimedes

simply included it as a challenging game.

But

then Netz was given a tangram by someone who had read about

his work. Its shapes were ordered differently to the way

he'd expected, and that sparked his own eureka moment. He

realised that Archimedes might have included the Stomachion

to demonstrate multiple solutions to a problem. This suggests

that the question Archimedes was tackling was: "how

many ways are there to complete a square, given the 14 pieces

of the puzzle?", Netz says. "This would be interesting

as an example of a very early study of combinatorics - the

study of the number of ways in which a given problem can

be solved."

Several

mathematicians raced to work out the number of unique solutions,

but it was Bill Cutler, a mathematician and computer scientist

based in Palatine, Illinois, who produced software that

came up with an answer: 536. This number was finally confirmed

on paper, using a method Netz believes Archimedes would

have approved of (SCIAMVS, vol 5, p 67).

For

Noel, one of the most striking discoveries was finding the

name of the 13th-century scribe whose work caused the researchers

so much difficulty. Noel and Netz dedicated their book about

the project to him: Ioannes Myronas. For Wilson, though,

there is still important unfinished business. "I can't

identify the hand of the scribe who penned the Archimedes

text itself," he confesses. "I'm still looking

for him. He's a wanted man."